First stop in Berlin: built at the end of the 19th century, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church was severely damaged in air raids in 1943. After some discussion about the best way to treat the remains of the structure, it was decided that a new building would incorporate the ruins of the original church, in order to commemorate its destruction.

The new structures, built around 1960, contrast in style, but complement the original in terms of massing. The new design provides a bell tower, an octagonal chapel, and smaller support structures. Since the completion of the new buildings, the church has continued to be used for worship, as well as functioning as a museum.

Scale model of the new church (excuse the glare)

The visual contrast between the old and new structures is very compelling, and has made the church a rather iconic tourist site. Given the already austere nature of the space by virtue of being a church, I think this project is well positioned for engagement with the site’s history and context. The chapel also hosts regular concerts, primarily classical and chamber music.

Gift shop built into the ruined portion of the church

View of the new chapel through a modern arched window in the ruined 19th century church

Next, while on our way to the Neue Nationalgalerie, I spotted this sign on the exterior of a fomer villa on Sigismundstrasse, whose facade was pockmarked with bullet holes. Wunden der Erinnerung, which translates to “Wounds of Memory,” is a project intended to acknowledge and preserve visible artillery marks on historic buildings. The project aims to commemorate the fraught past of buildings that were the site of combat, quietly inviting passerby to remember and reflect on this history.

The organization has placed at least 16 panels on historical buildings throughout Europe. I think this a great example of how through a very simple and accessible design move, the historical context of a building can be appropriately acknowledged, without necessarily impacting the building’s use or appearance. It appears most of the locations of these plaques are cultural, religious, or educational facilities, and I wonder how the effect would differ depending on its site. Would placement in a busy shopping area, or at a stadium or nightclub mean this information will fall on deaf ears? Or can interventions like these in unexpected places be even more impactful?

And next, my first main case study in Berlin:

Sammlung Boros is a project that feels representative of Berlin’s historical and cultural heritage. It was originally constructed as a civilian air-raid shelter using forced labor in 1942. Afterward, the structure was apparently used by the soviets to hold prisoners of war. Then, in the 50s and 60s in divided Berlin, it was used as storage for both textiles and produce, and became known locally as the “Banana Bunker.” In the 90s, the bunker was used “extra-legally” as an apparently notorious techno club. Acquired in the early 2000s by the Boros Foundation, it now houses Christian and Karen Boros’ contemporary art collection.

Waiting area

The gallery is accessible only by private tour, booked in advance. A private apartment has also been constructed on the roof of the bunker, a collision of public and private space that I found a little bizarre (during the tour, they even alerted us the the fact that we were being welcomed into “a private home,” though we only toured the galleries downstairs.)

The renovation created larger volumes in certain spaces through the strategic removal of floors and walls. This restraint came mostly from the incredible expense of demolishing the building’s thick reinforced concrete structural elements, but it also results in what I think is a successful dialogue between remaining and intervening spaces.

Credit to Casper Mueller Kneer Architects

The remaining texture of exposed concrete walls is featured throughout, with bullet holes on the exterior and the scars of demolished floors and walls on the interior. This texture contrasts starkly with new framed partitions and modern doors and windows. Some of the interior concrete has been deliberately painted white to match adjacent sheet rock, or left unpainted in contrast. The effect results in unique and thoughtfully varied exhibition spaces. These are effective gallery spaces, with dramatic and varying volumes, achieving a flexible space without the feel of a stark, blank canvas.

For me, this project represents successful adaptive reuse not only in terms of design, but in terms of commemoration: the continual reuse of the building and current acknowledgement of its varied past represents a cross section of Berlin’s complex and ever-evolving history. Even though the gallery isn’t particularly accessible, it’s affordable and public-facing enough to have built some notoriety, and established itself as a fixture of the city’s culture for those who visit long enough to dip below the popular tourist attractions. I would argue that this combination of cultural and historical presence is beneficial to the community.

However, I do think the building’s history could be commemorated beyond its verbal acknowledgement in the gallery tour. A plaque outside or a few informational panels in the lobby would be cheap, and really reinforce the building’s historical role without taking away from the art collection itself.

One last stop on day 2: north of the Berlin city center, a large area formerly between the inner and outer Berlin walls has become park space, now identifiable as Mauerpark, Park am Nordbahnhof, and the area of the Berlin Wall Memorial along Bernauer Strasse.

Today, Mauerpark is home to a Sunday flea market the draws swaths of people from all over the city, selling all sorts of goods, from street food to used clothing and antiques.

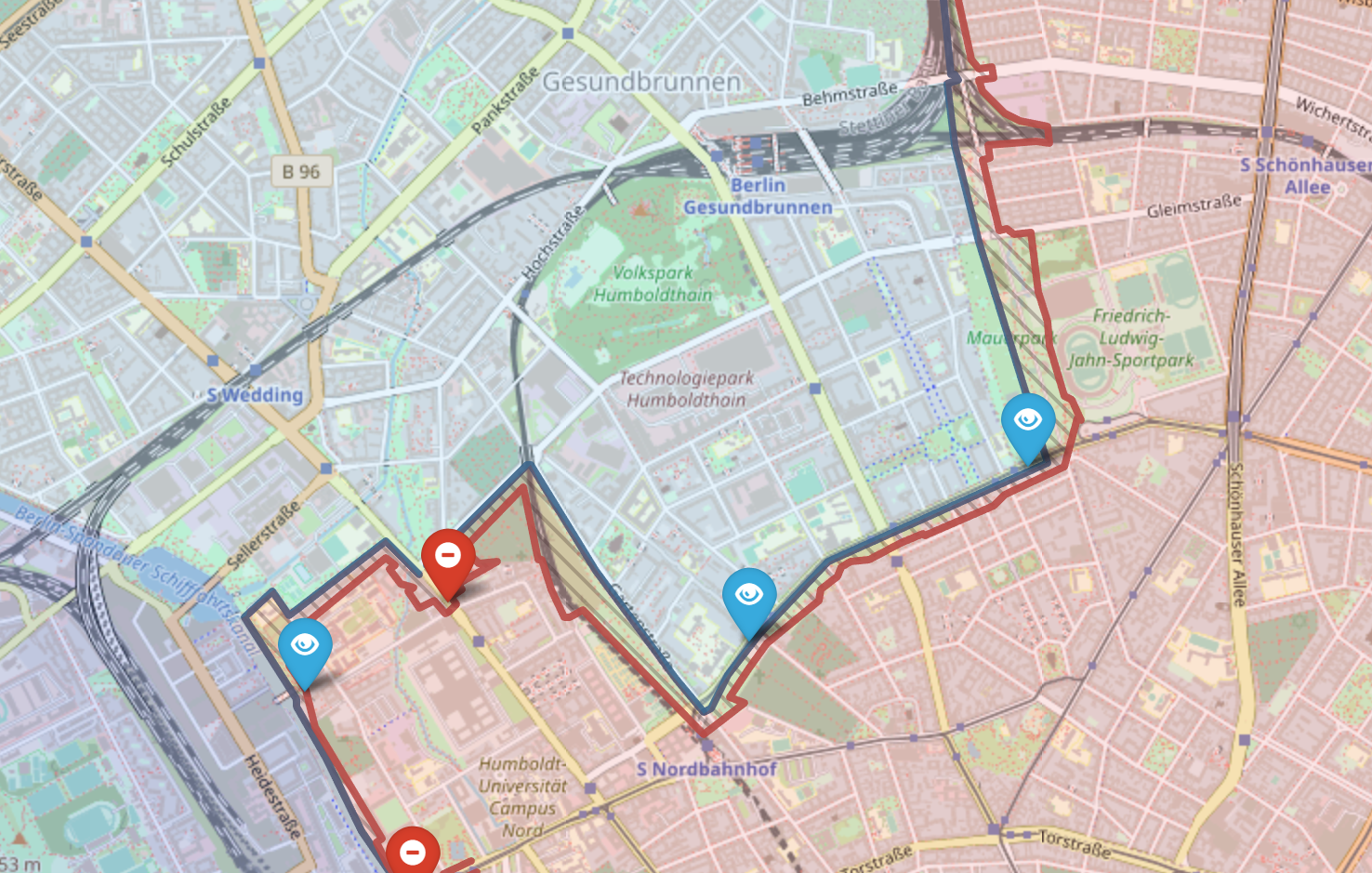

Map indicating former location of inner and outer walls from https://berlinwallmap.info/map/

Park am Nordbahnhof runs roughly North-South on the right, and Mauerpark on the left, with the Berlin Wall Memorial park connecting them in the East-West direction

It’s both exciting and perfectly expected to see the former demilitarized zone of Berlin’s wall used as a park: the area was cleared for so many years, and much of it is too narrow for significant building real estate. A park feels like a natural result of these physical effects, and a satisfying resolution to what was formerly a space representative of fear and trauma. I was also able to return a few days later to take a closer look at the Berlin Wall Memorial, which further addresses this historical context (more on that later).