Though the travel portion of this project is completed, I will be presenting my research at Berkeley sometime next year, and will continue to develop the ideas I’ve explored here, composing them into a cohesive presentation over the next few months. I’ve spent the past couple weeks reflecting on and organizing my research, and reading through my notes and posts (correcting occasional typos in the process).

More than anything, this project has emphasized to me the complexity of the role buildings play in our culture. How we experience buildings is influenced by their form and materiality, their social and historical context, and their established use. We react to buildings in ways that are sometimes intuitive, sometimes unpredictable, and for reasons difficult to recognize. They end up playing a role in our culture one way or another, regardless of their design intent.

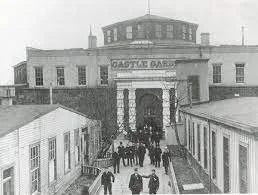

Sketchbook excerpt: “Levels of Historical Association”

Delving into themes of historical preservation and commemoration has helped me learn a lot about the role of a site’s history: a building’s current use might be informed by its history, or divorced from it. Sometimes the building’s history is all that matters, dictating future renovations, while sometimes its use and context continue to change over time, contributing new stories to the canon, and new possibilities in form and function.

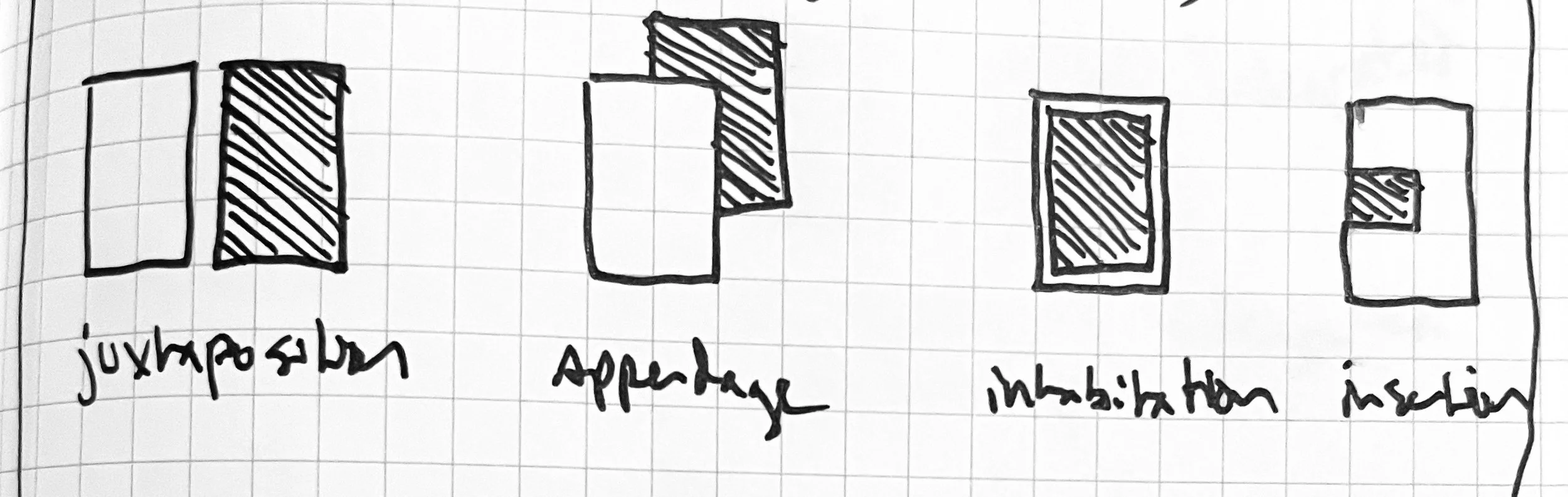

Sketchbook excerpt: “Modes of Reuse”

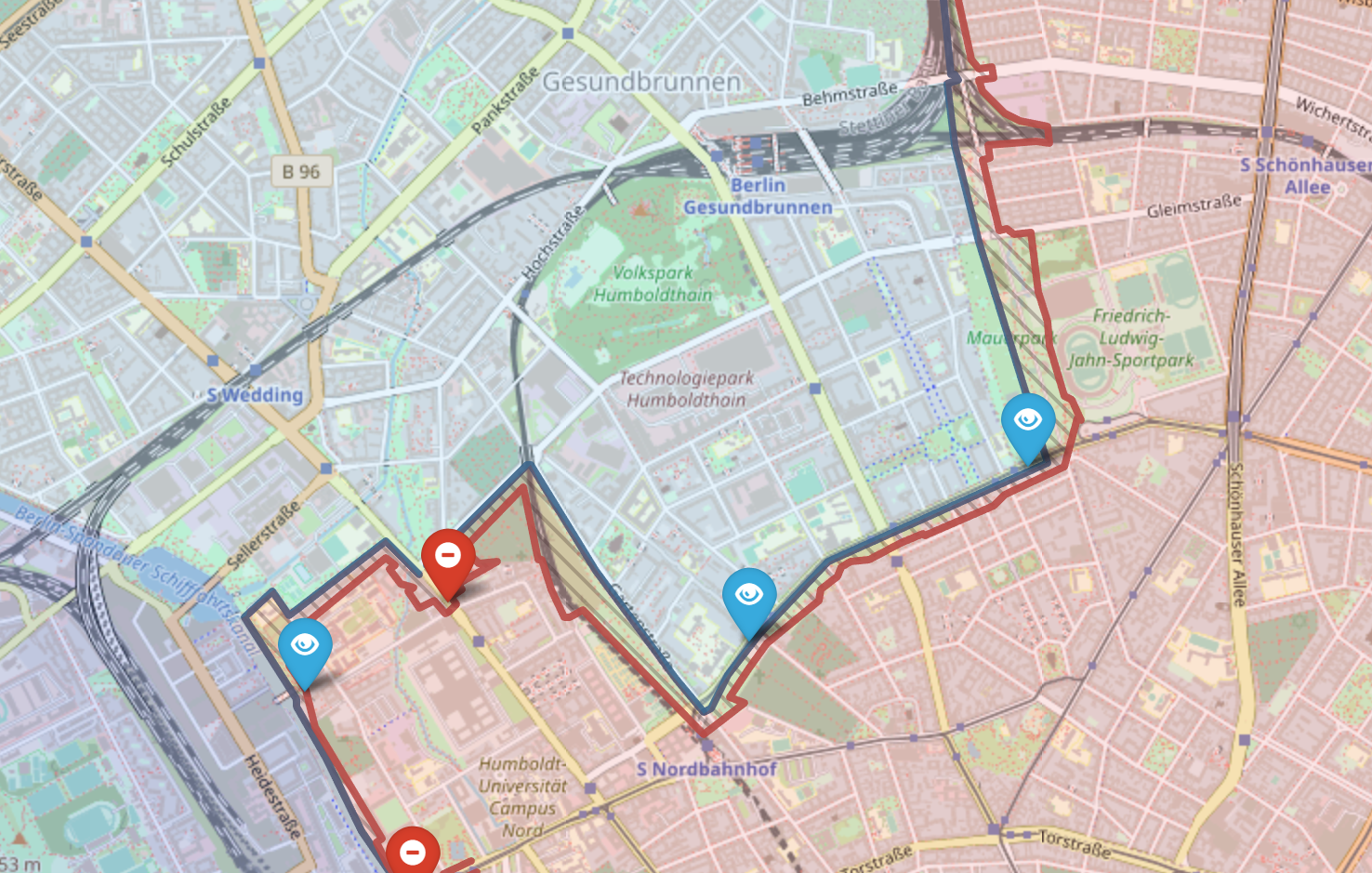

Though I’ve chosen several broad lenses through which to frame this project, I’m very excited by what I’ve found where these lenses intersect. Adaptive reuse, and within it, the preservation of a historic structure to some extent, is in itself an act of commemoration. Strategies for both reuse and commemoration are steeped in these questions of significance and individual engagement with the space. In adapting a building, we engage with its history, both physical and ideological.

This engagement in deeply personal. The challenge with both commemoration and preservation is that the parameters are defined by each person’s interpretation and experience. What’s important about the space? What does it mean to use the space in a new or different way? We cannot have complete certainty or objectivity when answering these questions, but what we can do is approach the project holistically, engage with the community and the history and do our best to account for the most significant factors.

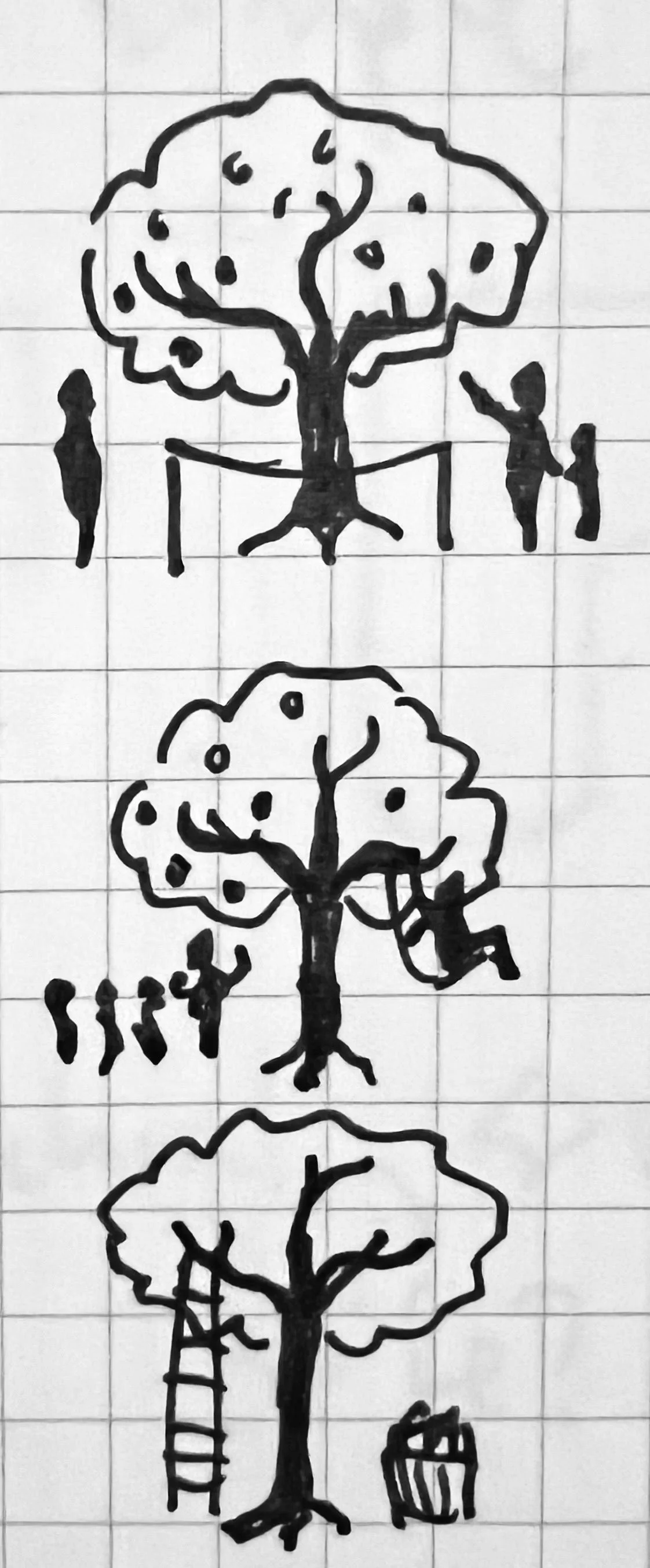

Sketchbook excerpt, modes of community engagement: educational, recreational, commercial.

When buildings successfully engage a community using these strategies of reuse, preservation and commemoration, they’re appealing to each user’s personal feelings, reactions and needs, and as a result, have the power to impact the greater community. How we remember and reuse historical buildings may change over time, but when we choose to reuse these buildings for community purposes, we have the opportunity to have an impact on a scale greater than the building itself.