The East Side Gallery is a remaining 1.3 km portion of the Berlin Wall along the Spree river, established as an open-air gallery in 1990.

This project both acknowledges the cultural role of the wall, and creates a site of interest within the community. Many of the murals featured directly address the subject of the wall itself, as well as topics related to the Cold War in general. The use of the wall as a gallery is in part also a nod to Berlin’s persistent graffiti culture, and has become an iconic tourist attraction.

I think the East Side Gallery represents a version of what I’ve found to be a popular method for reuse: employing historic buildings or ruins for art installations. This strategy is definitely cheaper than adapting the building, while arguably still beneficial for the community. Rather than allowing these remnants of the wall to crumble, invite graffiti, and fester as a reminder of issues unresolved, the gallery establishes the wall’s continued presence as a memorial to its lasting effect on the city.

Built in 1949 to honor the 80,000 Soviet soldiers who perished in the Battle of Berlin, the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower park is the largest outside of Russia. It also acknowledges the 25 million+ Soviets lost throughout World War II, the most of any nation.

Sarcophagi around the perimeter of the site hold the remains of 7000 soldiers, each monument emblazoned with a Stalin quote chronicling the hardships of the Soviet people (these quotes were not removed during the era of destalinization, likely for fear of defacing the graves.)

Though this is not a building, really, nor an example of reuse, I thought it was important to visit this site because I think it’s a unique example of commemoration. Many nations maintain graves of foreign soldiers whose remains were, for whatever reason, not repatriated (particularly as long as the nations involved have maintained good relationships). After WWII, Germany and Russia agreed to maintain graves of the other’s soldiers.

I found it particularly moving to visit the memorial now, as an American, in this moment when Russia is perceived globally as an aggressor, due to the ongoing war in Ukraine. The soldiers we commemorate at this memorial were also serving a leader who we now recognize as evil, who was responsible for a genocide of his own people - for many of the deaths, in fact, acknowledged by the memorial. And yet, the memorial remembers these people themselves, more so than their circumstances. The memorial site has been maintained, and will continue to be tended by Germany, regardless of the current relationship between these nations or their people. By continuing to acknowledge the lives lost, we continue to humanize those involved in these events, and ideally, learn from them.

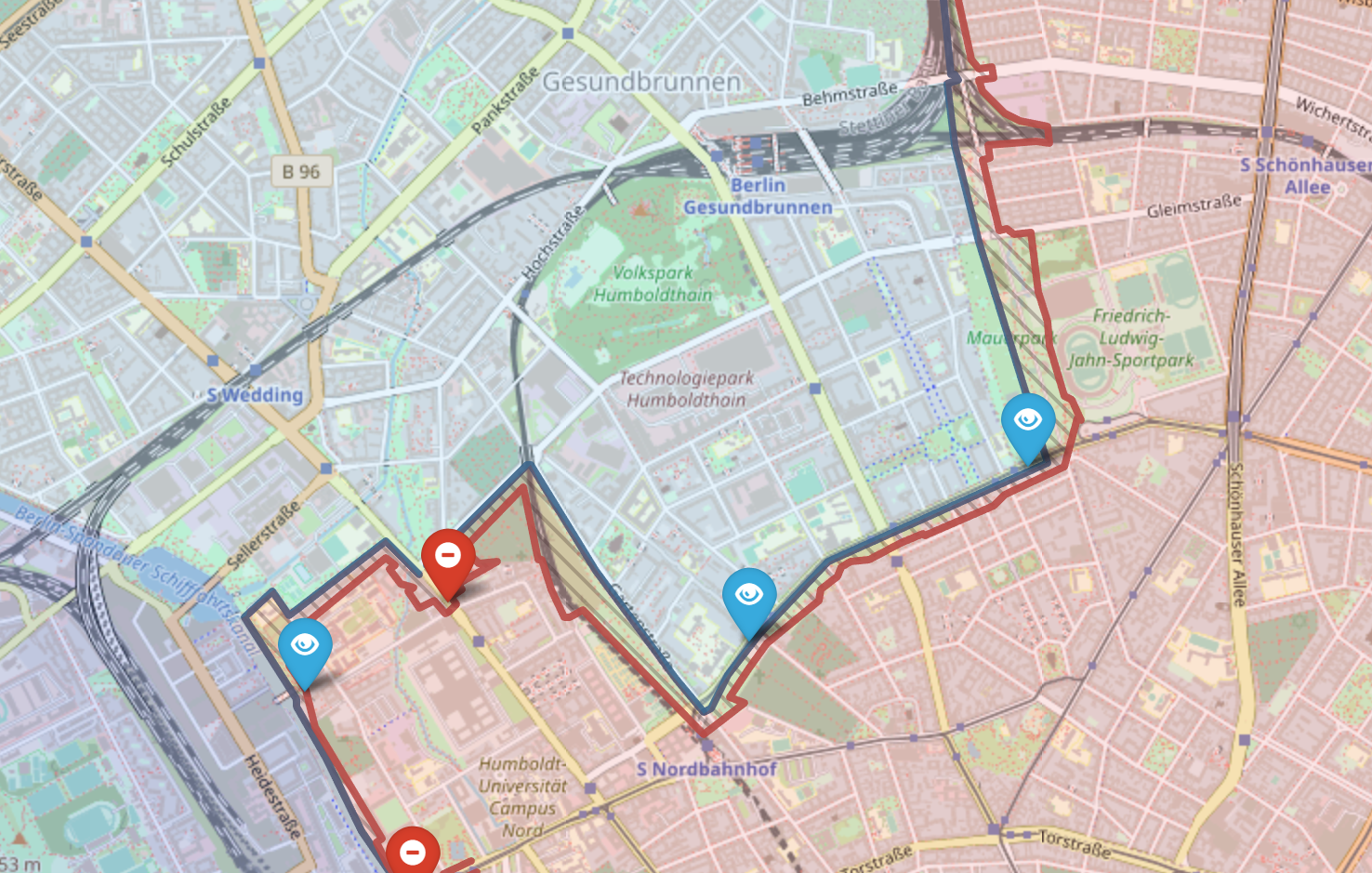

The Berlin Wall Memorial at Bernauer Strasse was inaugurated in 1998, and uses steel interventions to indicate the former location of the Berlin wall in this area, as well as other elements of the demilitarized zone, such as signal fences, watchtowers, former building footprints, and escape tunnels. The wall is delineated by a series of steel posts, while most of the other elements are marked by steel plates in various patterns and line types inlaid in the grass. These elements are paired with informational plaques and photographs, together telling the story of the wall, and its impact on this particular area of Berlin. Many who perished in their attempts to cross the border are memorialized specifically.

The installation stretches for over half a kilometer, defining a park that inhabits the former demilitarized zone. The steel elements are very illustrative, making the scale of the wall and the surrounding area very clear, while remaining subtle. The result is both a lovely park to stroll through, and an interesting place to pull over and spend a few minutes learning and reflecting.

I think this memorial is a really great example of a particular model of commemorating historic structures: in which the former location of a fallen structure is somehow acknowledged. In this case, the intervention doesn’t prevent the space from being occupied as a park, and has a powerful visual impact.

Tränenpalast, which translates to “Palace of Tears,” is a former Berlin wall checkpoint located adjacent to the Friedrichstrasse train station. The building has been converted into a museum about divided Berlin during the Cold War, with a focus on the specifics of what the experience of crossing through the checkpoint would entail, including reconstructions of passport booths, historical artifacts, etc.

The museum is defined by minimal architectural interventions, instead, the space is mostly true to its original form, divided into different sections by exhibit panels. Though this isn’t the most exciting site I’ve visited in terms of architectural design, I think the value of the museum lies in the ability to frame this history in the literal space where these processes took place.

Reconstruction of a processing booth

This project is representative of a category that has been prominent throughout my research, but especially so in Berlin: reusing a building primarily for a museum dedicated to historical events related to the building. Schindler’s Enamel Factory and the Museo Storico Della Liberazione, for instance, are not dissimilar examples, but in Berlin alone there are several similar cases. For example, the German Resistance Memorial Center is located in the former building of the Reich Ministry of Defense, in whose courtyard members of an anti-Nazi group were executed after an attempted coup. The Stasi Museum, which commemorates the history of the GDR and its effects, is located in the former Stasi headquarters in East Berlin. The Topography of Terror museum, which chronicles the Nazi regime, is located on the former site of the Gestapo and SS headquarters - though these buildings were destroyed during the war, the museum acknowledges their former presence. A remaining section of the Berlin wall has also been integrated into the site.

Source: https://www.visitberlin.de/en/topography-terror

This general strategy for reuse is a natural solution to the problem of buildings like these: the building’s context is adequately acknowledged, and the museum setting allows for other programmatic uses, such as libraries, research centers, art installations, etc. This is certainly a popular strategy, and given the large number of similar examples, enough to be a research project of its own. The reason I didn’t want to focus solely on this category of reuse is that a.) it often doesn’t lend itself to extensive architectural solutions. Rather, the preservation of the original building and incorporation of educational/commemorative material are the dominant priorities, and b.) I’m more interested in projects that push the use of these buildings further from commemoration alone, and more toward other community-oriented uses. The TEP center in New Orleans still exemplifies this for me: though the site’s history is adequately addressed, the building also fulfills some additional, completely separate community needs.